A non-invasive blood glucose monitor is being developed by a researcher and her team at Kennesaw State to make a normally painful and burdensome task easier for people with diabetes.

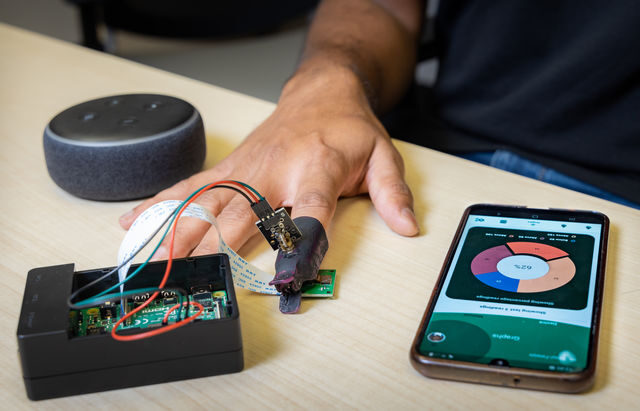

The device, developed by assistant professor of information technology, Maria Valero, is about the size of a credit card. It contains a sensor that shines a light through human tissue, typically a finger or part of an earlobe, to a camera on the other end which captures an image and estimates the blood glucose level with up to 90% accuracy.

“This is a sensor device that is non-invasive, that means that it doesn’t require anything related with blood samples or inserting needles in the body,” Valero said.

Valero and her team, which includes associate professor of exercise science Katherine Ingram, associate professor of information technology Hossain Shahriar and three students, have been working on developing this device since Jan. 2021 and are currently in the prototype stage. She hopes to make the device commercially available in about a year.

“My own father was a patient with diabetes, and he died for that,” Valero said. “So I always wanted to create something that makes the lives of people with diabetes easier.”

According to the CDC, one in 10 Americans has diabetes, which is the seventh leading cause of death in the United States and has cost a total of $327 billion in medical costs and lost wages. There is no cure for diabetes and those who have it need to frequently monitor their blood sugar levels to prevent health complications. Until very recently, the only way to do this was by pricking a finger to extract a blood sample.

“When I had to prick my finger when I was younger, it was a constant,” said Jackson Morris, a senior psych major at KSU who was diagnosed with type one diabetes when he was 4 years old. “It’s like death by a thousand paper cuts.”

Morris explained that he must check his blood sugar a minimum of five times or as much as 10 times a day. For 12 years, that meant pricking his finger each time he had to do this unpleasant but necessary part of his routine.

“If you have a friend that plays some kind of string instrument, you’re going to notice that they have really nasty callouses on their fingers,” said Morris. “I had those callouses on my fingers because of all of the pricking.”

Morris said that he was previously unaware that this technology was being developed, but that it felt good to know that something was in the works to help people like him.

“As an owl [KSU student], that’s honestly amazing,” Morris said, “Just to know that our science and tech division is doing something that impacts me directly makes me feel very in touch with my community and my university.”

Morris added that he would like to see more work in the area of continuous, automatic monitoring such as the kind his Dexcomdevice can do, but he is hopeful for this new field of non-invasive diabetes management.

Valero said that the best way to help her team continue to develop and make improvements on the device is by volunteering to collect data for the study.

“We need to continuously improve the models and continuously improve the way that we are getting the data, so we are always in need of volunteers,” Valero said.

Both people with diabetes and without it can volunteer to provide data by contacting Valero through her email at mvalero2@kennesaw.edu. Volunteers will be contacted for data collection and paid for their time according to Valero.