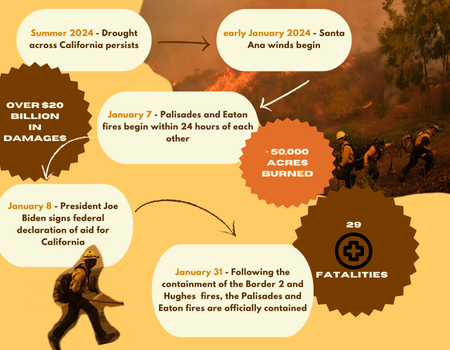

Southern California has been combatting a variety of wildfires, which have burned over 50,000 acres, resulting in 29 fatalities, and billions of dollars in economic damage.

Despite the annual occurrence of wildfires within California, the recent emergency has inflicted an unparalleled toll on the region after being impelled by a myriad of adverse climatic conditions and heightened urban development in fire-prone areas.

The region has endured a perennial drought since last summer and a series of intense Santa Ana windstorms which catalyzed the expansion of the first fires in early January.

It has also seen significant urban development and expansions within fire-prone areas in recent decades, a trend which has been exacerbated by the state’s ongoing housing crisis exposing more residents and infrastructure to the dangers of wildfires.

Thus, beginning on January 7th, several fires rapidly enveloped Greater Los Angeles, with local authorities issuing numerous evacuation orders, as thousands of acres and structures were scorched.

According to NBC News, almost 200,000 residents were forced to evacuate the affected areas within the initial phases of the fires and the resources of state and local authorities were quickly overwhelmed.

According to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, over 300 wildfires ignited, with the most destructive being the Palisades, Eaton, and Hughes fires.

The first, the Palisades fire, formed as a small brush fire in the affluent Pacific Palisades neighborhood near Malibu prior to expanding across over 23,000 acres and destroying over6,800structures. It also claimed twelve lives.

The Eaton fire decimated the communities of North Pasadena and Altadena and burned over 14,000 acres, killed at least 17, and damaged and destroyed over 5,000 structures, while the Hughes fire, located in north Los Angeles County, burned just over 10,000 acres.

Examples of other lethal blazes which have affected the region include the Kenneth Fire, which damaged the town of Ventura, and the Border 2 Fire in the Otay Mountain Wilderness near the U.S.-Mexico border—both of which have individually burned more than 1,000 acres.

Dr. Max Crocker, an Assistant Professor of Biology and Environmental Science at Kennesaw State, spoke with the Sentinel on the intense toll of the recent wildfires, claiming, “The fire regimes are part of a process that happens over and over again, but this current fire season has been very destructive in terms of property and life. It’s just a horrible situation… because you’re looking at neighborhoods and businesses that were destroyed due to the fires.”

The Sentinel also received comments from KSU student Andrew Lynch, who expressed similar sentiments. “It’s complete disaster really,” he lamented, “In the end, California’s unlikely to get funding when they want.”

Another student, Nasier Brown was unsurprised by the occurrence of the disaster, saying, “I was pretty sure it was gonna happen at some point considering California and the west coast in general experience fires a lot.” Despite this, he expressed remorse stating, “It’s terrible, I wouldn’t wish that on anyone.”

The magnitude of this destruction the fires inflicted in Greater Los Angeles resulted in an urgent, but turbulent response from local, state, and federal authorities.

Within the initial days, the Los Angeles County Fire Department hurriedlyrequested aid from neighboring counties after its 29 city fire departments were overwhelmed.

California governor, Gavin Newsom, soondeployed the state’s national guard to assist, and a detachment of incarcerated firefighters was also dispatched.Private firefighters were also involved, being heavily recruited among the area’s wealthy residents to protect their properties, despite attracting criticism.

The area also received extensive support from the federal government, with former President Biden issuing a federal disaster declaration in early January to allocate funding to recovery and cleanup efforts. He also ordered the deployment of firefighting personnel from the Department of Defense and military, and theFederal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) opening multiple disaster recovery centers to assist victims. Additional teams of firefighters arrived from states such as Utah, Washington, Oregon, New Mexico, Montana and Arizona to collaborate with local divisions.

Assistance also came from abroad, with the Canadian government sending numerous firefighters to the region in addition to water bomber aircraft. Mexico also sent various teams of firefighters, and other countries, including Ukraine,Iran and Japan, offered to provide operational and humanitarian assistance.

Though such assistance was widely embraced positively by government officials, some viewed it as a sign the situation was inexorable. “It’s embarrassing that countries like Canada have to offer help us,” Brown claimed, “because we should have the supplies to handle it on our own. We’re the richest country in the world.”

Such sentiments stimulated controversy as emergency efforts were met with fraught challenges. A focal point of contention was the water supply within certain areas, especially Pacific Palisades, where the local fire hydrant system had been exhausted and alocal reservoir laid empty after closing for repairs months earlier, leaving the community more vulnerable to its wildfire’s expansion.

The broad expansion of debris from the blazes also contaminatedthe water supplies of cities such as Pasadena and compromised the Los Angeles County sewer system. This left many residents without access to clean water in the most extreme periods of the disaster.

Infrastructural damage, such as power outages were also severe, with Southern California’s primary utility provider, Southern California Edison, reporting that around 414,000 of its customers were without power within the first week of the fires.

These challenges were compounded by exceptionally extreme Santa Ana winds which reached speeds of 80 to 100 miles an hour in some areas and hindered efforts to extinguish the fires from the air as they expanded, in addition to threatening vehicle and air traffic.

Additionally, the budget of the city’s fire department had been significantly reduced for the current fiscal year, a measure that greatly stifled key fire prevention operations, such as bush-clearing and residence inspections. This widely criticized development coincided with price increases and shipment delays for firefighting vehicles were a further impediment.

Recurring illicit drone activity in many of the impacted communities also complicated firefighting efforts andlootingbecame widespread within affected communities such as Pacific Palisades and Encino, with at least 29 arrests being made for the offense.

Air quality levels deteriorated due to the dispersal of smoke by the region’s powerful winds, putting many residents and firefighters at risk of exposure tocarcinogens and conditions such as dry eye syndrome and respiratory illnesses. Agencies such as the Los Angeles Department of Public Health also claimed that the spread of toxic chemicals through the air put locally produced foods at risk of contamination.

Issues such as these tremendously compromised public order, the operations of firefighters, and the authorities as Southern Californian communities attempted to withstand the crisis.

Nevertheless, the disaster’s broader impact has been defined by the political and economic disputes it instigated.

The most salient occurred between recently President Donald Trump and democratic leaders in California, primarily Governor Newsom and Los Angeles mayor Karen Bass.

On social media, Trump attributed the issues with the Pacific Palisades fire hydrant system to mismanagement of water policy on the part of Newsom, claiming that they improperly distributed water to protect anendangered species of Delta Smelt. This was met with fervent criticism from Newsom, Bass and local experts and officials, who clarified the system’s failure was largely caused by the intensity of the fires.

Another key dispute centered on the role of private insurers responsible for financing property damage caused by the wildfires. With insured losses from the fires totaling over $20 billion, numerous providers such as AllState and State Farm cancelled home insurance policies in fire-prone communities, with some such as Pacific Palisades seeing a 69.4% non-renewal rate. This left countless California residents without home insurance in the wake of the wildfires, and many politicians and journalists have criticized the state government’s policies for creating an economic moral hazard which instigated the matter.

“That’s pretty messed up,” Brown commented on the matter, “[the victims] need quick aid very badly.”

As these developments garnered similar reactions among California locals, Dr. Crocker commented on the consequential, but less preeminent role played by insurance companies. “Insurance corporations are very involved, and they have important roles too,” he began, emphasizing their influence relative to government authorities, “The insurance network of the world is an important thing to be aware of, and it’s harder to know where they’re coming from because they’re not on the news.”

Moreover, as with similar crises, misinformation disseminated widely across the internet as the wildfires unfolded, with false claims that the fires were exacerbated by factors such as forest mismanagement, and AI-generated images of fake fire scenes becoming popular, namely among critics of the state’s democratic government. The magnitude of the misinformation and disinformation prompted Governor Newsom to launch a webpage called CaliforniaFireFacts.com, which features refutations of various falsehoods concerning the fires, though many continued to spread due to rife political polarization.

Lynch expressed disappointment with the abundance of misinformation online. “It’s a little bit strange,” he remarked on the forestry falsehoods, “because the federal government owns the majority of Californian forests.” He went on to reference other accusations that he had heard, affirming, “they just don’t make any sense.”

Moreover, highly publicized research found that the intensity of the fires had been exacerbated by the ongoing climate crisis.Studies from institutions such asUCLA have claimed that various environmental causes of the fires were linked to rising global temperatures caused by augmented greenhouse gas emissions. This stimulated increased discourse about climate change and has become a profound source of concern among the public.

However, Dr. Crocker offered an alternative perspective on the matter. “It isn’t actually necessary to look at it in that perspective,” he said, “Climate drives a lot of ecosystem processes, including wildfires in mediterranean environments like Southern California. Those are ecosystems that have evolved within fire regimes, so wildfires in themselves are just as normal as photosynthesis. It’s just a part of how nature works.”

He proceeded to describe how long-term climate variations could alter wildfire frequency and intensity over time, but that it was difficult to attribute specific incidences to climate change.

“Climate is not weather,” he remarked, “and wildfires are due to longer term things, so there are different timescales involved.”

The dozens of deaths, thousands of displacements, burned structures and exorbitant financial costs caused by the destructive wildfires will present longstanding problems which may take several years to be fully solved.

Dr. Crocker spoke about how a vital means of achieving such a solution was through fostering sustainability. “But” he added, “an important question is what does that look like?”

With the fires now contained, Southern California looks to rebuild on the backdrop of conflict between state officials and the White House.