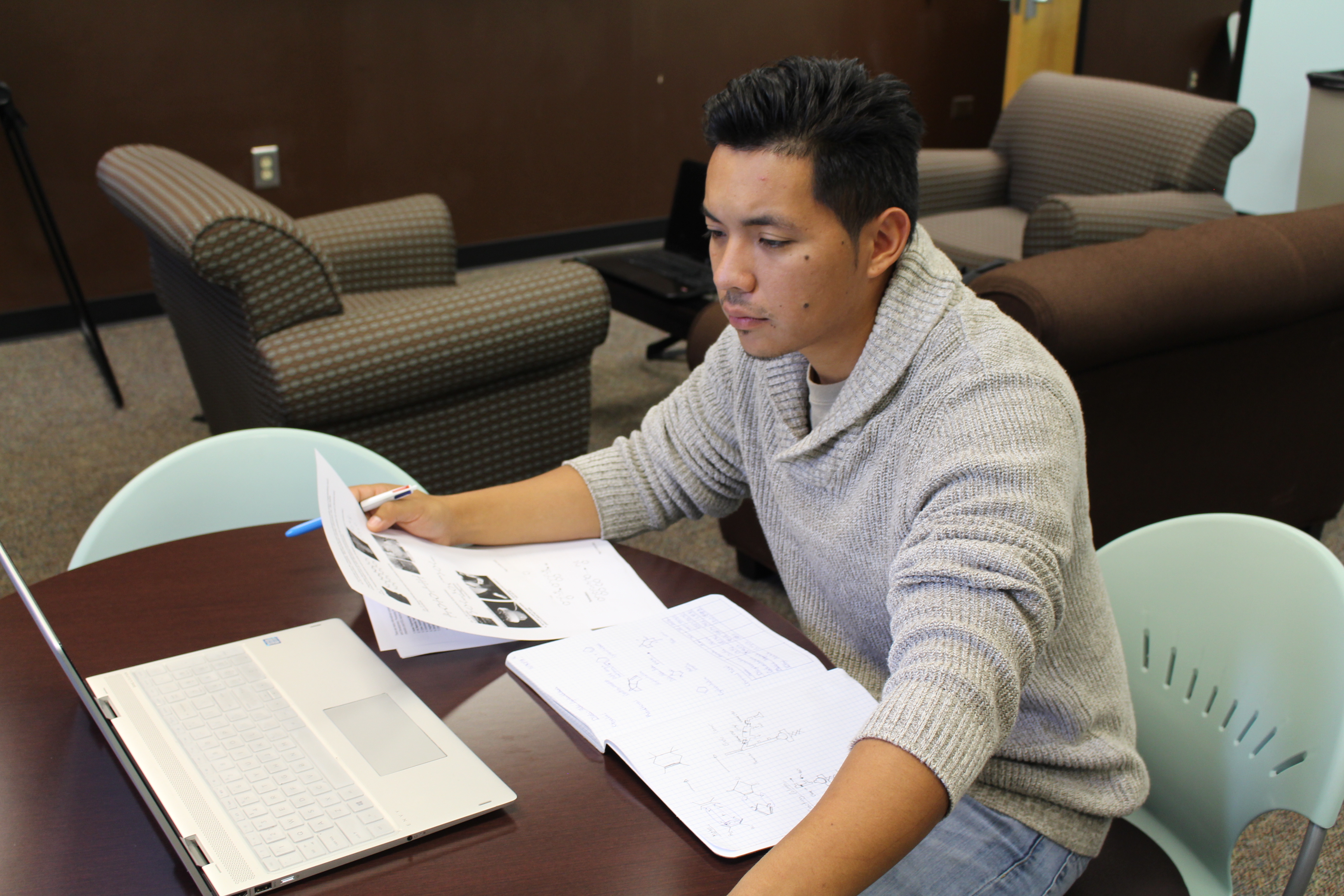

Tony Albarca, a 23-year-old student at Kennesaw State, has big dreams.

He’s in his final year of college, recently became engaged and hopes to pursue a career in veterinary medicine. He’s also an undocumented immigrant, and fears that the Trump administration’s recent decision to overturn the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program — which allows Albarca to remain in the United States — may put a halt to his dreams.

Albarca, a senior biology major, immigrated to the United States from Guatemala with his family when he was five years old. He’s able to attend KSU because of DACA, which grants undocumented immigrants work permit eligibility, a social security number, a driver’s license and protection from deportation as long as they entered the U.S. before their 16th birthday.

He heard about DACA through the news and from a high school advisor — before that, he had no idea how he was going to manage to get an education after graduating high school. He had originally hoped to attend the University of Georgia, but the Board of Regents forbids undocumented immigrants from attending the state’s top five schools. Georgia is one of only three states to implement such a ban.

Albarca’s life — and the lives of 800,000 DACA recipients around the country — changed drastically on Sept. 5 when President Donald Trump announced he would be rescinding the Obama-era program. Albarca was upset to hear about the president’s decision, fearing for both himself and his younger sister, who is also a DACA recipient.

“It was really sad, but I kind of expected it with this administration,” Albarca said. “They’ve been putting out so many negative policies that it was only a matter of time that DACA was going to be taken out.”

According to Trump, there will be a six-month delay before the program is officially rescinded, which he said would give Congress a window of time to come up with a permanent replacement to the program if they wished. Albarca, however, is skeptical about the seemingly-benevolent gesture.

“He’s not really creating a means for Congress to actually do something about it,” he said. “He’s just pushing the blame to them if nothing happens.”

According to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, immigrants whose DACA statuses expire before March 5, 2018, can request a renewal as long as they do so by Oct. 5. This buys Albarca some time, but without legislative change, his status will still eventually expire — and that has accelerated his personal life greatly.

Albarca recently proposed to his girlfriend, and he hopes he will be able to obtain citizenship once he is married. No matter what happens though, one thing is clear to him: his life is here, and it will remain here even after his DACA status expires.

Once that happens, he plans to live under the radar to avoid deportation. He said he wants to go about his regular life without attracting the attention of any law enforcement, but should he face deportation, he won’t go down without a fight.

“I will try to fight it because I’ve never committed any crimes, I’ve done my taxes every year, I’m even trying to start my own landscaping company and contribute back to the economy,” Albarca said.

Albarca sees the removal of DACA as a step backward for the U.S. and believes the future growth of the U.S. economy will be negatively affected because students who could have graduated and given back will no longer be attending school.

Although this is a troubling time for DACA recipients, Albarca said he’s uplifted by those around the country who have come to his defense. He mentioned a candlelight protest in hosted in Centennial Olympic Park in Atlanta recently and said that he is glad to see people from different states united together to speak out against the removal of DACA.

Still, there is likely a long road ahead for him.

“People say that I committed a crime because I crossed the border,” he said. “I don’t have a criminal record, but to them, that is a crime.”