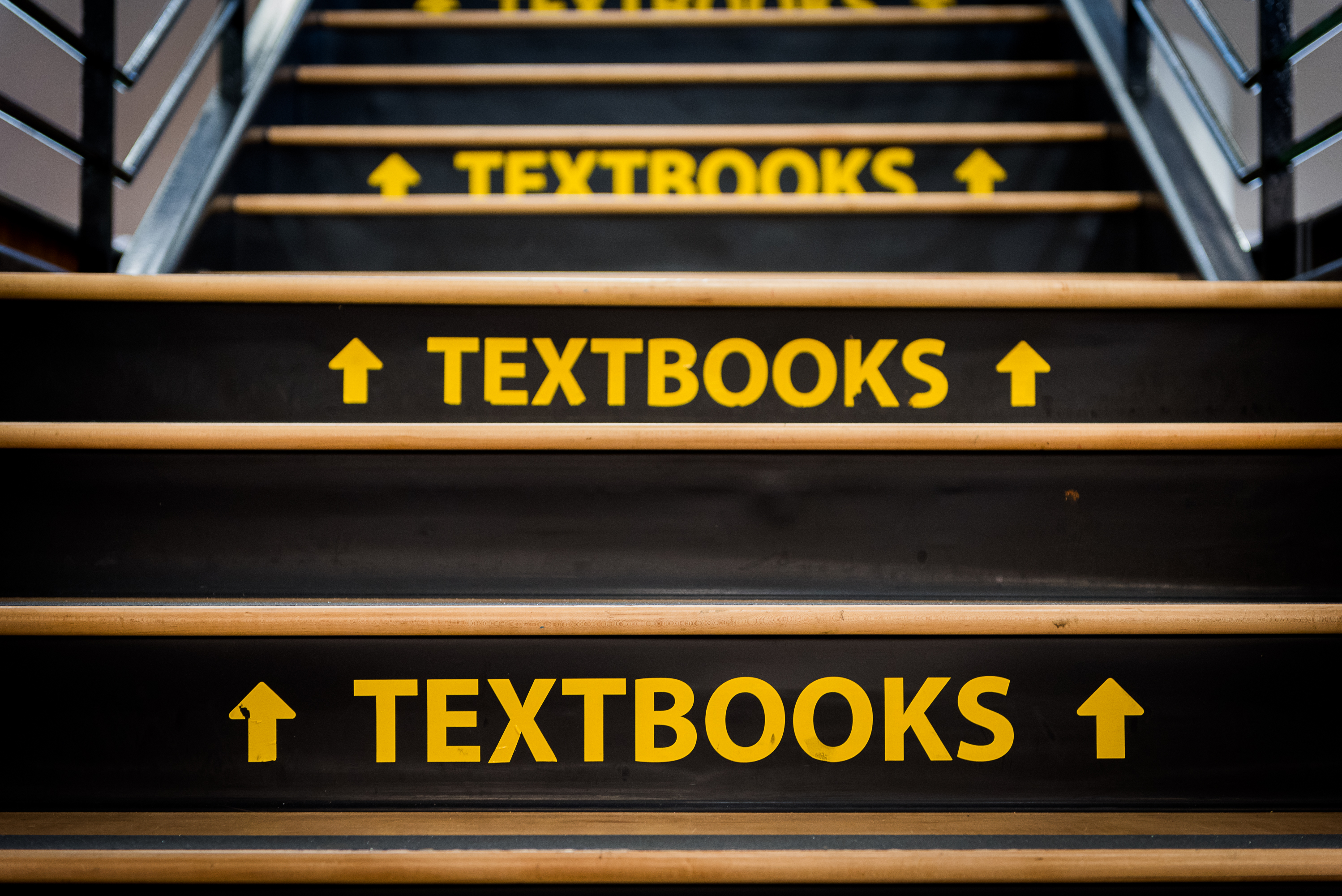

It’s no secret to students at Kennesaw State University and at colleges across America that the prices of textbooks are astronomically high.

In fact, the average cost of a college textbook has increased by 73 percent since 2006, according to a study by Student Public Interest Research Groups. Nearly one-third of students in the study reported that they used financial aid to help pay for their textbooks.

In a historical context, textbook prices have increased by 812 percent since 1978, according to AEI, a public policy think tank.

The problem gets bigger when we consider that almost every class requires a textbook, and, in most classes, the assigned textbooks are mandatory. Some teachers even build their class around a specific book. Many online courses are taught almost entirely through a third party instead of through the university, like a companion program to the textbook.

It’s hard to understand why many universities require students to buy textbooks, and it’s even more difficult to figure out why universities sell textbooks directly.

The KSU bookstore’s website claims that “nonprofit campus bookstores consistently benefit students with course materials at the lowest possible price.” Some campus bookstores may be registered as nonprofits, but it’s quite a stretch to say that they offer the best prices, especially compared to used bookstores and online stores.

Don’t believe me? Check out bookbinder.com and see for yourself.

Still, this leaves a few seemingly unanswerable questions:

- If university bookstores aren’t offering the best prices on books, but they also don’t make a profit, then what is the purpose of their operation?

- Could it be possible that some university bookstores are listed as nonprofits simply because they are the property of their respective nonprofit schools, while in actuality their only function is to generate revenue for their university?

- If that’s true, how much profit is really made by on-campus bookstores?

Universities need to step up and offer the public full disclosure about exactly where their money comes from and exactly how it is spent.

While the amount of money made by public universities in relation to book sales is debatable, the publishing companies’ profit margins are even more elusive. Mark Perry from AEI states that, “over the last 34 years, college textbooks have risen more than three times the amount of the average increase for all goods and services.”

According to research gathered by Priceconomics.com, textbook production costs are very fluid and largely depend manufacturing and editorials fees, as well as on individual bookstore markups. Even with these varying costs, I can’t imagine how the publishing industry can justify an 812 percent increase since 1978.

No matter how these prices are decided, the results are the same. Millions of college students are in massive debt, and paying thousands of dollars on books certainly doesn’t help. Learning shouldn’t be a debt sentence, and books shouldn’t cost more than furniture.

In order to figure out how to reduce the prices of textbooks, we need transparency from universities and publishing companies. We also need universities and publishing companies run by individuals who genuinely want to help students, not make a profit at their expense.

In the meantime, if you are struggling with textbook prices, here are some helpful tips on how to spend as little as possible.